“The beautiful––first to surmise its existence, elusively in the world through time, and here and there in your life these unexpendable experiences that defy the norm and the reality, then the miracle of wanting it, and the character to seek it, and the possibility of even creating it––this is a spiritual battle, first with the total of one’s self and second with almost the total of one’s environment” (Merizon, The Relevance of the Arts to Current History, 10-16-76).

Peace, quiet, and order is what I seek for. Beauty, if possible. And the ultimate would be something spiritual.

As Armand continued to paint he struggled with concepts such as integrity, beauty and truth. To Armand’s mind, Schnabel’s integrity was closely linked with beauty, beauty in how one interpreted a musical piece, beauty in how one painted it. Yet, Armand was also well-aware that beauty can be burdened with a darker side. Regarding the capriciousness of that, Armand speaks about the startling contrasts that can occur. First, “just the joy of being alive. You witness that in a child. And then the sheer aimless, sinister, arbitrariness of a tragic accident happening to that child. The absurdity of who’s going to be killed, who’s going to be sucked up in a tornado or an earthquake. The endless, meaningless, little tragedies and great tragedies.

“My point is: You have to be truthful and honest to face reality as I put it. You have to be able to hold on like that. Even though, in your moods, depending on maybe how much sleep you’ve had, in your moods you can’t possibly give each one equal and fair time. The tension of it. You definitely can’t. There are times that we can only take that which is lovely and sweet because we can’t face up or even hardly want to acknowledge the horrendous.

“Though man is capable of devising great tragedies, unintentional tragedies occur all the time. I’ve had tears in my eyes right by this window where I’ve seen a beautiful bird fly right into it and break its neck. It lies out there fluttering for a minute. Then it dies. There’s no rhyme or reason for it [meaning its sudden death]. It’s ‘miserable’. [Here you have a] beautiful creature, magnificent in its body function. The sound it can make! The pureness of those notes! And then be deceived by a piece of glass that reflects the sky so perfectly that the bird is deceived and figures he is just going to keep flying into space. Instead he breaks his neck.”

Armand continues, “I’ve picked up birds even downtown that lay on the sidewalk that died. I took one home. I kept it in the freezer, gorgeous creature. That’s when I could see it in great detail. It would be like a preliminary study of, say, an Andrew Wyeth, careful drawing, very precise monochrome study.” Pointing to his work, he said, “I named this ‘A little REQUIEM to the BROWN CREEPER .’ It illustrates the inane stupid tragedies that await so many beautiful joyous creatures. See what I mean?”

He goes on. “Now, I know, I’ve done paintings just for the joy of joy. Beauty. I’m trying to achieve a color. That’s good for itself. But I was thinking about the contradiction here. At the same time I’ve done paintings, both the natural and the man-made, like the painting called ‘Inexorable.’ In it you can see the willfulness of man to destroy. War. War. War. It’s as old as the human will. It’s as old as the world. . . I would classify it as a political statement, more of a protest” (Dornbush/Zandstra Interview, 7-10-02).

Again, in “Love, Anger, and Farewell” Armand depicts the destruction that man imposes on one of his most beloved subjects, Lake Michigan. Here you can see raw sewage spewing out into Lake Michigan polluting one of our nation’s most treasured natural resources.

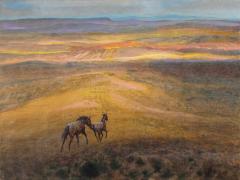

“On the other hand I’ve painted something that’s just lovely to look at for itself--for its majesty, ‘The Sun Chasers.’ There’s dignity there. Just to behold that. To be out there. To sit quietly. To see the carved land like that--the kind of atmosphere it has. You see, that’s the other side of it” (Zandstra Interview, 10-31-09).

In “Antithesis” he depicts the harmonic melancholy of Beethoven’s well-loved “Pathetique,” its musical staff centered on top of a disharmonic frieze. In the frieze you can see a line of Red Cross ambulances, tiers of ticky-tacky houses, a gridlock of high rises, and an iron-bound trail of railroad cars. They are overshadowed by a triad of smoking nuclear towers which ironically anticipate the Chernobyl spring—a nuclear disaster that occurred shortly after the painting was completed. Above the frieze, backlit in the snow, a hunter looms above the carcass of a big wolf, its life blood draining into the tundra. Nearby his partner is caught in a trap, her foot bleeding while their pup stands by with bowed head. Hunters converge, some walking, others bearing down on snowmobiles. In the top left we see another wolf that appears to be howling in protest to hunters on horseback who are packing out another gutted carcass.